Bootstrap 01: Loader

2025-9-28

For now, the only way we can program the computer is by toggling machine code on the front panel. We would like to load data on from a storage medium such as paper tape or audio cassette.

1 Programming on the Altair

If you haven’t read the first part, the Aquila is my attempt at replicating the Altair 8800 which is an old computer based on the Intel 8080 CPU. I’m trying to bootstrap from nothing and this article is the first step.

Because toggling programs with the front panel can quickly become tedious, I need to store them on external storage (punched tape, cassette) and have a bootloader program to read them back in the computer’s memory. This program will have to be inputted by hand each time the system is started. I also need a simple program to dump memory onto the storage medium, but it won’t be used much as is since it will later be part of the system.

In step 2 I will write a monitor program that will have to be loaded from the front panel once to be dumped, and later loaded by the bootloader. Step 3 will extend that monitor, but the modification will be entered using a keyboard and the existing monitor functions, one extension could be a built-in dumper.

2 Code Writing Process

For now, everything will have to be hand-assembled because I’m not allowed to use an existing assembler, I would have to program one myself and it would have to run on the Altair. The 8080 doesn’t have relative jumps, we have to put absolute jump addresses everywhere, it makes writing machine code by hand quite annoying sometimes.

The 8080 has the same instruction set as the Z80 which added some

extra instructions, in fact there was a Z80 option for the Altair. Z80

assembly differs a bit but the actual machine code is mostly

retrocompatible. I’ll be using the Intel mnemonics since I got familiar

with them making my emulator and I’ll write hex numbers with an

H suffix. I like the instruction table provided here.

I’ll assume you have some familiarity with assembly and I won’t explain the basics like what are jumps and labels. I’ll still be explaining some specific instructions and key architectural quirks. The code will be shown with the hex dump on the left and the assembly on the right.

3 IO Devices

At this point we can only load data by poking values with the front panel switches. We would like to use a serial connection instead so data can be loaded from (and dumped to) a storage medium. Back in the day people would have used punch tape or audio cassettes. Well, I don’t own a Model 33 Teletype, but I have a Minitel terminal and I can emulate a paper tape. I’ve also made a modem to store modulated signals with a cassette recorder.

The CPU can’t communicate directly with these devices, instead it talks to a serial interface card. The most popular was the the 88-2SIO (“2SIO”) card which provides two serial ports that can be connected to terminals or punched tape devices. There is also an older 88-SIO (“1SIO”) with a single port.

The 88-ACR Audio Cassette Interface uses the same interface as the 1SIO to store data on audio cassettes using a standard tape recorder. In fact it is made of two cards: a 1SIO and a modem. The serial signal from the 1SIO is modulated by the modem, and the modulated signal is recorded on the cassette. The signal from the tape can later be demodulated and then decoded by the serial card to be read by the CPU.

From the programmer’s perspective all devices work in pretty much the

same way. The card’s registers are bound to IO ports which can be

accessed using the IN and OUT instructions.

Before accessing the data register we need to wait for the card to be

ready by looking at the status register.

4 Program Requirements and Design

Let’s write two programs for loading and dumping programs. These must be small because they will have to be loaded by hand. They should also stop automatically, instead of going past end of tape and potentially overwriting or other parts of memory. Ideally the loader should jump automatically to the start address when loading is complete.

One difficult part is knowing how many bytes to read. The widely distributed bootloaders from the BASIC manuals of the era limited the length to 256 bytes and the address to a 256 bytes boundary. The data was also placed in reverse on the tape so starting at the end address (page + length), loading could stop when the low address byte reached zero. At this point the address register contains the start address and can be jumped to. An other limitation with this approach is that the address has to be set by hand in the loader code, and have to be written (with a pen) as metadata on the tape. Other ways to solve this problem include putting the values in a header at the start of the data, or including a second stage loader without the limitations.

A second difficulty is that with paper tape, the read head won’t necessarily be aligned with the start of the payload when starting the program. The tape reader will read the empty space located before the payload as zeros, they need to be skipped. With magnetic tape it’s slightly different, empty space isn’t read as zeros but there is always some noise that gets in the input buffer before the payload. Waiting for a special start byte placed in front of the payload should work. We can use the length of the payload as the special value since it will already be in some register.

5 Implementation

| 15 .. 8 | 7 .. 0 |

|---|---|

| A | FLAGS |

| B | C |

| D | E |

| H | L |

| SP | |

| PC | |

HL registers contains the 16bit

address used in some instructions.

The program is straight forward. The load page and length is first

loaded in the main address register HL, like on the Z80,

8bits registers can be paired. Bytes are inputted (port 07H

for ACR, 01H for 1SIO) until the start byte is found. Then

bytes are inputted and stored at HL address until the

length reaches zero.

The data available bit (bit 0) of the status register (port

06H for ACR, 00H for 1SIO) is checked using a

rotate right RRC, the bit is saved in the carry flag. A one

means no data is available so it is followed by a jump if carry set

JC to continue waiting.

0000 ORG 0000H

0000 21 endaddr LXI H, endaddr ; End addr

0003 DB06 lead IN 06H ; Get status

0005 0F RRC ; Input available?

0006 DA0300 JC lead ; Loop if not

0009 DB07 IN 07H ; Get data

000B BD CMP L

000C C20300 JNZ lead ; Loop until start found

000F DB06 read IN 06H ; Get status

0011 0F RRC ; Input available?

0012 DA0F00 JC read ; Loop if not

0015 DB07 IN 07H ; Get data

0017 2D DCR L ; Dec len / next addr

0018 77 MOV M, A ; Store to [HL]

0019 C20F00 JNZ read ; Continue if L!=0

001C E9 PCHL ; Jump to start address

001D ENDIt’s 29 bytes long:

21 len page DB 06 0F DA 03 00 DB 07 BD C2 03 00 DB 06 0F DA 0F 00 DB 07 2D 77 C2 0F 00 E9

The final PCHL (E9H) can be replaced by

HLT (76H) if the data isn’t intended to be

executed. The BASIC bootloaders used additional tricks to merge the two

loops and be smaller by handling the leader bytes differently but that

would make the dumper harder. I’ve also thought using the

RSTx instruction to get one byte subroutine calls but it

doesn’t really save. I feel it’s small enough for now, I can always

adjust it later.

6 Dumper

The dumper follows the same logic as the loader, except byte are

loaded from RAM and outputted to the serial device. Writing the start

byte is also easier than waiting for it. I assume the data register is

clear to send at the beginning, later I check bit 7 of the status

register is using left rotate RLC. We have to be careful

with the order of operation so we don’t get a off-by-one error.

0000 ORG 0000H

0000 21 pagelen LXI H, pagelen ; End address, page + length

0003 7D MOV A, L ; Output start byte

0004 D307 OUT 07H ; Assume the port is ready

0006 DB06 loop IN 06H ; Get status

0008 07 RLC ; Output ready?

0009 DA0600 JC loop ; Loop if not

000C 2D DCR L ; Dec len / next addr

000D 7E MOV A, M ; Load data

000E D307 OUT 07H ; Put data

0010 C20600 JNZ loop ; Continue if L!=0

0013 76 HLT

0014 ENDThe resulting machine code is 20 bytes long:

21 len page 8D D3 07 DB 06 07 DA 03 00 2D 7E D3 07 C2 06 00 76.

7 End-to-end Test

Test protocol:

- Toggle in the dumper

- Toggle in some data, for instance the string “ABCD”

(

41 42 43 44) at location0100H(end address0103H) - Dump the data and check the tape contents

- Turn off and on the computer to clear/randomize the memory

- Toggle in the loader

- Load the tape and check memory

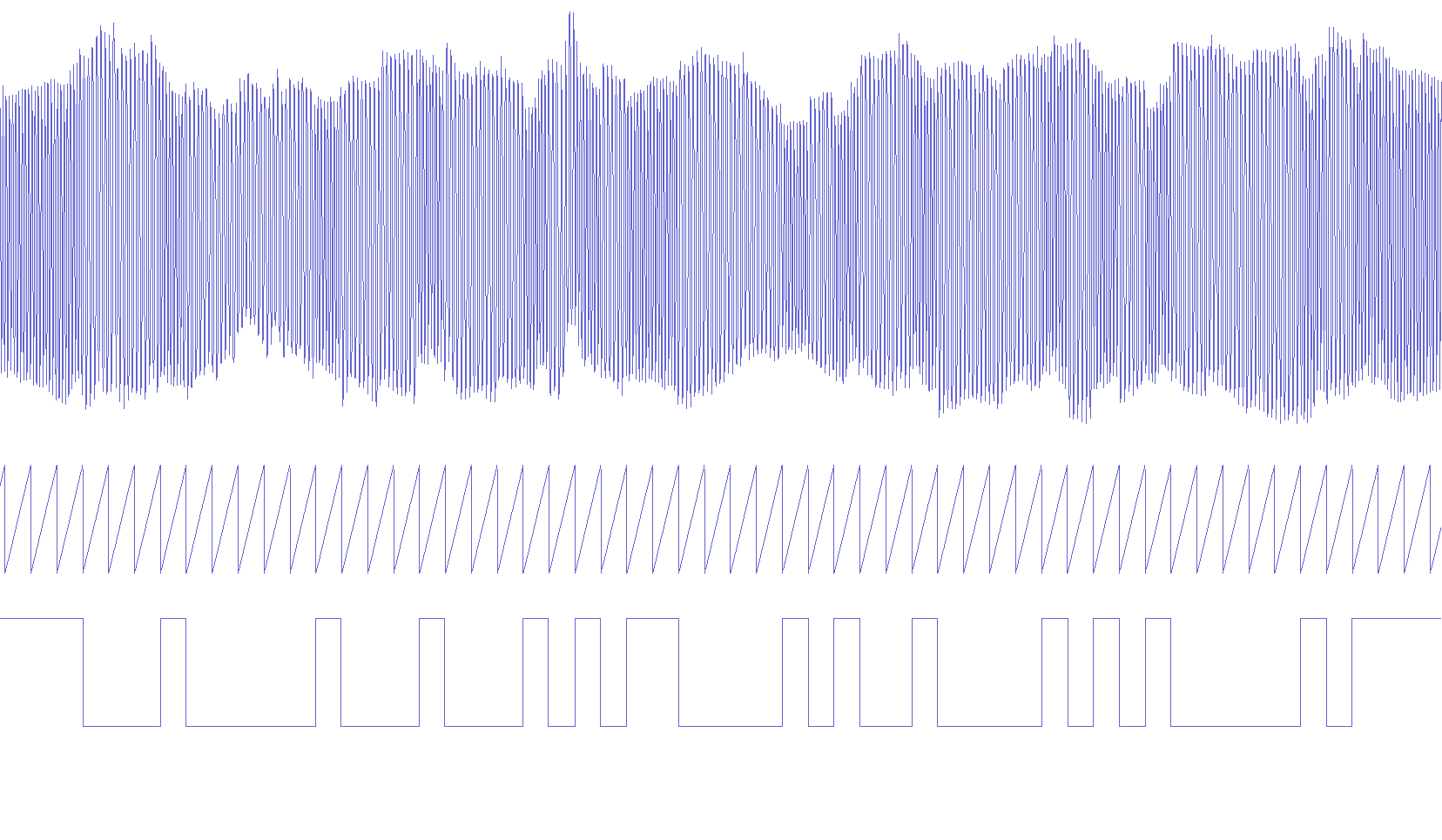

From the string “ABCD” placed in reverse by the dumper, knowing the serial signal is 300baud 8 data bits least significant bit first with a 0 start bit and a 1 stop bit (8N1) we expect the following bit sequence:

...11111 idle

0 00100000 1 4

0 00100010 1 'D'

0 11000010 1 'C'

0 01000010 1 'B'

0 10000010 1 'A'

11111... idleThis is indeed what we observe when looking at the waveform. Bits are encoded as a high pitch for one and low pitch for zero. If we squint we can see where the line crosses zero more often (ones) and where it crosses less (zeros). I put a 300Hz sawtooth clock signal as an indication to help seeing where sampling happens.

I was able to load back the data, I don’t have anything exciting to show for this part, it worked.

8 Conclusion

In this article, I designed and tested a tape loader and dumper for my Altair 8800 replica, the first step in my bootstrap project. In the next article I will make a simple monitor so it’s easier to change memory values and write longer programs with a keyboard.

It took me a long time to get back to this project. I published the first version of this article almost one year ago. Back then I hadn’t built the modem and was using the tape emulation. Now I hope to be able to work on it more often.